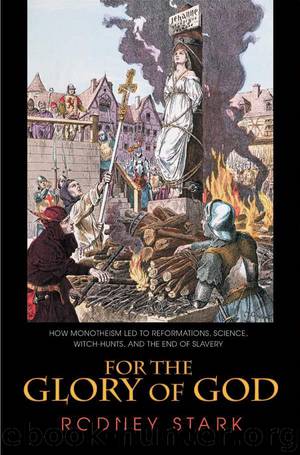

For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery by Rodney Stark

Author:Rodney Stark

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2015-01-27T00:00:00+00:00

HERESY AS WITCHCRAFT

In some parts of Europe the word for witch was gazarius, which is a corruption of Cathar, and in many areas it was wuadensis or vaudois, both being corruptions of Waldensian. In the Jura region, the word for witch in local dialects was derived from the word for heretic.159 This linguistic association reflects the fact that Europeans initially conceived of witchcraft, and became concerned about it, as a function of organized heretical movements. Thus in 1258 Pope Alexander IV advised inquisitors that they “ought not intervene in cases of divination or sorcery unless these clearly savour of manifest heresy.”160

It was in response to Cathar doctrines concerning Satan’s immense power and control of worldly affairs that Christian leaders began to worry about actual pacts with the Devil and to condemn the Cathars for satanic dealings. Moreover, it was in response to heresy that the practice of burning people at the stake became common. In 1184 Pope Lucius III endorsed burning heretics by quoting John 15:6: “If a man abideth not in me, he is cast forth as a branch, and is withered; and men gather them, and cast them into the fire, and they are burned.” In 1198 Pope Innocent III identified dissenters as guilty of “treason against Christ.”161 And it was the search for Cathars and Waldensians that encouraged belief in witches’ sabbats, since these heretics often did, of necessity, meet in secret places, often at night, where they performed heretical rites—to which cynical propagandists and gullible theologians added elaborate claims about orgies and depravity: “kissing cats and frogs, calling up the Devil, and fornicating in an orgy with the lights turned out.”162 Recall from Chapter 1 that the Church nearly always accused heretical groups of sexual improprieties, and this easily carried over into tales about the sexual degeneracy of “witches.”

Of course, notions about witchcraft had been around for many centuries, perhaps since the earliest human communities—although these notions were lacking in satanism. Furthermore, the idea that Satan tries to tempt and recruit followers was an old one too—the New Testament tells of the temptation of Christ and reports incidents of possession by evil spirits. Indeed, from early times the Church employed exorcists to deal with that problem. Satanic ties had also often been imputed to the Jews and to various early gnostic heresies, beginning with Simon Magus. Hence there was an orthodox background for satanic suspicions. Then, in the fourteenth century, charges of satanism began to appear in European politics as various high officials, including bishops, were condemned for causing the early death of kings and conspiring against popes.163 Most of these charges were insincere, as in the many instances when Pope John XXII (1316 to 1334) burned his opponents within the Church, or when Philip IV (1268–1314) of France claimed that he had burned grand master of the Knights Templar, Jacques de Molay, and Geoffroi de Charney, preceptor of Normandy, for worshiping the Devil.164 In some other cases, the prosecutors may have been sincere. Either way, what is important is that the idea of consorting with Satan was becoming credible.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Buddhism | Christianity |

| Ethnic & Tribal | General |

| Hinduism | Islam |

| Judaism | New Age, Mythology & Occult |

| Religion, Politics & State |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31339)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30936)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30891)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16635)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13059)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11907)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10910)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4541)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4426)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4401)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4282)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3845)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(3764)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(3637)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3572)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3518)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3440)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3338)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3260)